That New York Times “critic at large” A.O. Scott chooses to write an annotated, or annotating, commentary on Judge Biery’s recent, widely-shared order in the case of young Liam Conejo Ramos both is and is not telling. Writers pick newsworthy topics and the Conejo Ramos case was newsworthy. Critics need texts, and the order qualifies. Of course it’s both unsurprising and significant that Scott selected this text, with these politics, for praise rather than some other text. It wouldn’t be crazy to say, as a conservative or right-wing observer might (noting, as always, the widening distinction between the two), that this is indicative of the Times’s worldview. And it wouldn’t be crazy for the drafting chambers to feel pleased about having the opinion receive the plaudits. (I say “chambers” to honor the traditional convention of treating judges as not doing their own writing, although this judge has a long history of issuing non-staid opinions and thus may well be the primary drafter.)

But it would be too easy for both–the critics finding confirmation of their views, and the chambers feeling that the acclaim confirms the value of the opinion–to exaggerate the point. In an attention economy, everything is fodder. Judicial opinions with little pictures attached to them, presidential AI slop depicting that president (in a military aircraft, of all things) bombing his own fellow citizens, random acts of kindness, SNL skits, murders, and dog shows–they’re all ultimately just disposable fuel. The modern version of the Warholian dictum should state that every news item is someone‘s “BREAKING: EMERGENCY PODCAST.”

That said, with a couple of important caveats, I must say this opinion is pretty darn poor. It asserts too much, too casually, in too little space. Like a graduating student’s high school yearbook page, it ends up cramming a bunch of quotations and references together all hugger-mugger, which diminishes rather than enhances the effect of each one. Pace Scott, it’s not especially erudite. Nor is it especially eloquent. Eloquence doesn’t require fancy talk, but even the attempt at more demotic prose is a bit stumbly. Beginning a paragraph with the kind of sentence fragment you might use orally or, God help us, on Twitter (“Civics lesson to the government:…) is plain talk, but also kind of junky. I happen to think many officers in this regime do in fact have a “perfidious lust for unbridled power,” although that’s perhaps a little shortsighted; some of them also want to betray their own country for money. But, even if that’s so, this case is not an especially apt illustration of that point. Viewed favorably to the petitioner, the case is not so much about the lust for unbridled power as it is about cruelty and lawlessness in the unbridled exercise of power. And the fragmentary sentence “With a judicial finger in the constitutional dike”–well, that’s just bad writing.

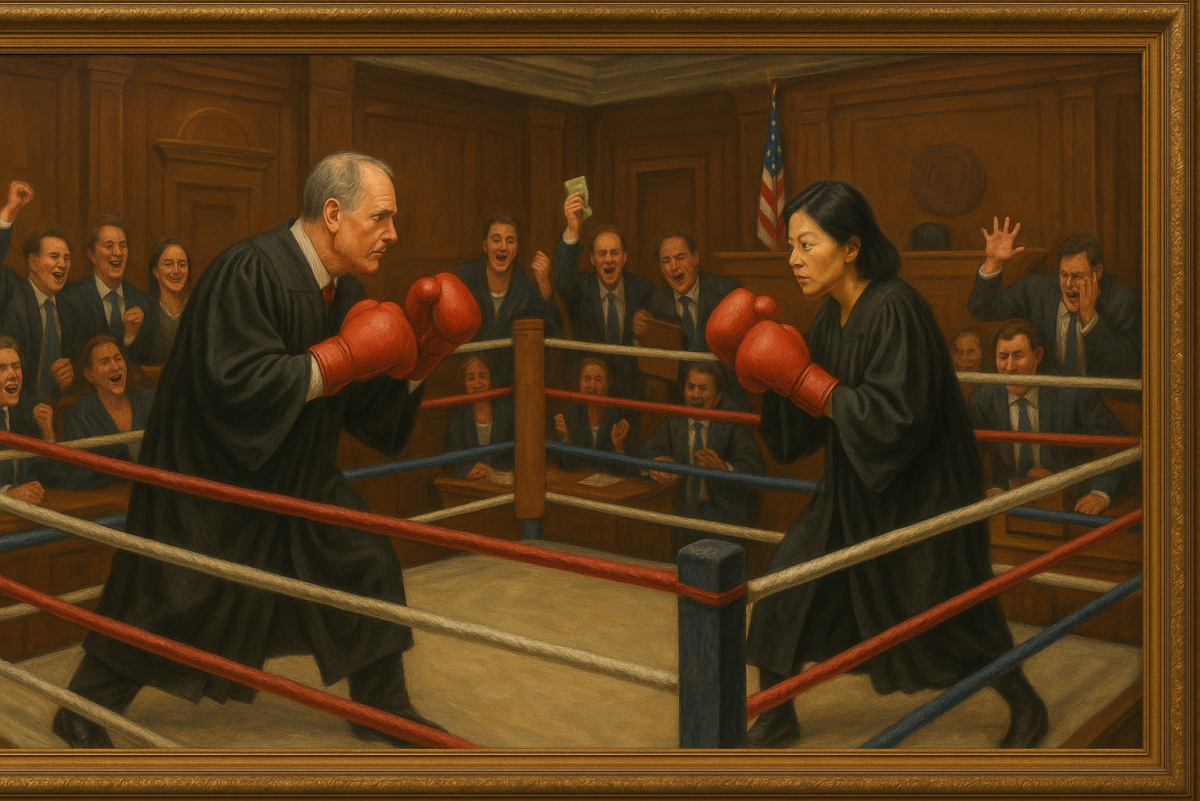

Above all, notwithstanding the photo (adorned, not objectionably but unnecessarily, with a couple of Bible citations), as a rhetorical and persuasive document it reflects the bizarre writerly strategy of omitting its best resource: the facts. A recounting of the attempted use of the boy to affect entry and the detention of a pregnant woman, the paramilitary garb of the forces, the alternatives to detaining him, any conflicting factual statements by the regime and its representatives (there are always conflicting statements in this regime), and any conflicting or inconsistent legal positions taken by that regime (ditto) would have been more powerful and could have been accomplished with equal economy. As this drop-in-the-ocean example from the District Court of Minnesota illustrates in its first two paragraphs, simply recounting the facts can be much more powerful than more sweeping language. And even opinions that offer more general observations about lawlessness are made more effective when the opinion does most of its work through the facts. Judge Biery’s order–quotes, photographs, and all–is much more forgettable and less significant than this opinion setting forth in unsparing factual and procedural detail this regime’s eagerness to imprison people who are victims of or have helped stop human trafficking, as well as its fundamental incompetence and malice.

I appreciate–this is my first caveat–that Judge Biery, like many federal judges across the country, has had to wade through thousands of individual cases, involving actually existing human beings, in which they are confronted again and again with this regime’s lack of seriousness about law enforcement, law enforcement training, immigration law and policy, human decency, and the well-being of the Justice Department, the Constitution, and the rule of law. That doesn’t transform a poorly written opinion into a well-written one. But I ought to acknowledge that Judge Biery’s evident frustration and anger are far more rooted in consequential daily experience than mine.

My other reservation is that many readers obviously have praised the quality of the writing in Judge Biery’s order. Obviously, they’re wrong and I’m right. (And not everyone who has praised the order was praising its writing; some were merely praising the fact of the order and its outcome, and for others it came down almost entirely to the photo.) But it’s still worth noting, because it raises the question of the audience for judicial opinions.

Biery’s history of opinion-writing suggests that he didn’t suddenly adopt a new writing style for the age of social media. But the notion that a judge might, or even ought to, seek the attention of that audience seems much more taken for granted today and has given rise to any number of judicial horrors in prose. Regardless of his intent, Biery’s yearbook-page-style order is chock full of strung-together bits that are just the right length and mentality for snipping and sharing. But going after the social media audience is a bad idea that invites cheap eloquence, violence to the English language, or both. Given that most people are not social-media addicts, it’s not even an especially democratic or populist approach.

Questions of social media aside, the momentary popularity of the opinion on the left side of the ledger might suggest that the opinion’s style was most likely to gain the approval of people who already disapprove of the regime. I am happy to assume that Biery wasn’t specifically seeking the approval of that audience, but was merely giving vent to what I’ve already said is understandable outrage. Far be it from me to blame anyone, let alone any lawyer and decent citizen, for giving voice to outrage over lawlessness, thuggishness, corruption, dishonesty, incompetence, hatred of Christian values, treason, anti-conservatism, illiberalism, conspiracism, cowardice, vanity, vulgarity, and a stew of antisemitism, racism, more-than-vaguely-white nationalism, and other creepy neopagan bigotries, all of which, for this regime, are basically just another day. But surely, if one even ought to seek a particular audience, that’s not especially the right one to go after. If you are outraged by these things, surely you would benefit more from convincing one additional person to feel disturbed or angry than you would from convincing ten people who already feel that way to become more disturbed and angry, which is also basically just another day.